dotScale 2016

25 Apr 2016After dotSecurity last Friday, it is now time to go to dotScale. This follows the same pattern as the dotCSS/dotJS conferences. One short (one afternoon) on the Friday and one longer (one full day) on the next Monday.

As usual, this took place in the Théatre de Paris. The main issue of the last dotJS that took place here (the main room getting hotter and hotter along the day) was fixed, which let us completely enjoy the talks. There were more than 800 attendees this time.

Mickael Rémond

First talk was by Mickael Rémond, about the Erlang language. It was a high level talk, explaining the history of the language.

It started in 1973, in big telecommunication firms. It follows what is called the Actor Model. Each actor has a single responsibility and can send messages to other actors. It can also create new actors and process its list of incoming message in a sequential order, one at a time. Each actor is an independent entity and they share nothing.

By definition they are scalable, because they all do the same thing without being tied to any specific state or data. You can distribute them on one machine, or across several machines in a cluster.

In 1986, Erlang was officially born. It added a second principle of "let it crash". As actors have one responsibility, then do not have to bother about handling errors. If it fails, it crashes, and the whole language embraces that. Other actors can be added on top of the first to handle the errors, but the main responsibility of each actor does not care about errors.

More than ten years later, in 1998, Erlang was finally released as open-source. The most interesting features of Erlang are not the language itself, but all the primitives of it that are implemented by the Erlang VM. Today new languages are born on top of Erlang, that uses the same VM, like Elixir (done by the core contributors of Ruby on Rails, it is gaining some popularity lately).

Overall the talk was a nice way to start the day. Even if not directly a story of scaling, it was great generic knowledge.

Vasia Kalavri

Next talk continued on that generic knowledge pattern, with Vasia Kalavri who told us more about graph databases. I didn't really see the link with scaling here either, I must say. The slides are available here.

In graph databases, relationships between objects are first class citizen, even more than the objects themselves. You can run machine learning algorithm on those relationships, and infer recommendation, "who to follow"-like features. Even search in a graph database is nothing more than a shortest path algorithm. Even the Panama Paper leaks was mapped using a graph database.

When we start talking about big data, we often think about distributed graph processing. Vasia was here to tell us that distributed processing was not always the right answer for graph databases. Because we are mapping relationships between objects, the size of the dataset to map does not have a direct correlation with the final size of the data in memory. You might think that with your TB of user data you might need a huge cluster to compute everything. Actually, to process its "who to follow" feature, Twitter only needs 64GB of RAM. And that's more than 2 billion users. When you start thinking you'll need a distributed cluster to host all your data, please think again. The chances that you have more users than Twitter are actually quite low.

If storage space is not a relevant argument, maybe speed is? You might think that using a cluster of several nodes will be faster than using one single node. Actually, this is not true either. The biggest challenge in building graph databases is cleaning the input. You will aggregate input from various sources, in various formats, at various intervals. First thing you have to do is clean it and process it, and this is what will take the longest time. When you think of it, your data is already kind of distributed across all your sources. Just process/clean it where it is before sending it to your graph database.

Then the talk went deeper into the various applications of graph databases, like iterative value propagation, which is the algorithm used for calculating things like Google PageRank. You basically compute a metric on each node and aggregate it with the same metric from the neighbor nodes.

It then went into specifics of Flink, Sparks and Storm but I didn't really manage to follow here, except that the strength of Flink was its decoupling of streaming and batch operation while Spark does streaming through micro-batches.

Not really what I was expecting from dotScale here, but why not.

Sandeepan Banerjee

After that the ex-head of data of Google, Sandeepan Banerjee, talked about containers and how they deal with state.

His point was what we've all heard for the past two years. How Docker is awesome, and how Docker still does not answer the question of stateful data. How do you handle your dependencies in a container? How do you handle logging from a container? How do you run health checks on containers? Where do you save your container database?

As long as your container only compute data coming to it, and sending it back, you're fine. But as soon as you have to store anything anywhere, your container starts to be linked to its surroundings. You cannot move it

When an issue is raised in production, it would be nice to be able to get the container back with its data to your dev environment and run your usual debugging tools on it, with the production data. It also raises the question of integration testing of containers. How do you test that your container is working correctly, when it is talking to other micro-services?

In a perfect world, you would be able to move a container with its data from one cloud provider to another, as easily as if there was no data attached. You could move it back to local dev as well and share the data with other teams so each can debug the issue in their service, with the same data from production. But we're not in an ideal world.

He then gave his solution, which still does not have a name, of a way to organise containers by grouping them and moving the whole group at once. Even if each internal container will be stateless, the group itself will have knowledge of the associated data and relationships between containers, thus becoming stateful.

This solution would be based on a git-like approach, where the snapshots would not only contain relationships and data, but would also include a time dimension. This would allow you, just like in git, to get back in time and reload the snapshot like it was two days ago, and share a unique reference to that moment in time with other teams. He also talked about using the same semantics of branches and merges across snapshots.

He went even further talking about a GitHub-like service where you could push your container snapshots and share them, versioning your infra as you go and integrate it into CI tools to deploy a whole network of containers with a simple commit.

Overall this looked like a very promising idea, even if we are really far from it. A few other talks during the day mentioned the Git approach of branches and unique commit identifier as a way to solve a lot of issues. I hope this project will be released one day because if it actually fixes the issues that were raised, it will greatly help. Still, today it felt more like a wish list than anything real.

Oliver Keeble

Next talk was one of the most interesting of the day, one that makes you put in perspective your own scalability issues. It was about the Large Hadron Collider of the CERN, and how they manage to handle all the data they got from the experiments.

The LHC is the world's largest particle accelerator, it takes the form of a 27km long underground tunnel where they collide particles at the speed of light, and analyse the results. It's an international scientific collaboration. When the collision happens, things happen, things disappear, and the only things that are left are the data the machines where able to capture.

Because such an experiment is a huge scale, they need to capture as much data as possible per experiment. They have more than 700 tons of detection devices, that record data at a rate of 40 millions times per seconds. That is a lot of data to capture, send and process.

Because there is so much data, they know they won't be able to capture all of it, so they have to make estimates based on what they captured, and extrapolate from that. To do so, they have to calibrate the machines with empty tests, to see the amount of data they manage to capture from a known experiment. Then, it's just drawing a statistical picture for when they will do it with more data.

In addition to data that can fail to be recorded, data transmission can also fail. Sending so much data from the source of the experiment to the machines that will process it will obviously incur some data loss in the transfer. To counter that, they have a validation mechanism to check that the received data is not corrupted. It makes the transfer slower, but is needed because every piece of information counts.

They also have a dynamic throttling of the data sent. They analyze in real time the percentage of success of such checksum validation, and if the percentage improves, they will push more data. If it decreases, they will push less, which should dynamically alter the throughput to be the most efficient. As the speaker said:

You'll always be disappointed by your infrastructure, then better to embrace it.

Because of its international structure, the data analysis of the data is done in parallel in every parts of the globe, along what they call the grid. Machines in all lab research facility can help computing the data. They just register to a queue of available machines, announcing their current load. The CERN on the other end will submit jobs to another queue and attribute each job to a matching machine. Once the job is finished on the machine, it will just call home with the results and final results of all jobs are merged into a new queue.

It takes 25 years to build such a collider, and they are building a new one, a 100km ring around Geneva, so they expect to catch 10 times more data in the future.

That was the kind of talk I like to see at dotScale. Real world use cases of crazy scalability issues and how to solve them.

Lightning talks

After the lunch break was time for the lightning talks. The overall quality was much better than at dotSecurity.

Datadog

First talk was by a guy from Datadog, but he never advertised its company directly. Instead he used the same colors as the company logo, and talked about a dating website for dogs. You know, a place to date a dog… It was not completely obvious, so fair enough :)

His talk was about the need to monitor everything, not only some key metrics, because you never really know what metrics you should be careful about. By logging more and more data, you can correlate parts of your infra/business together. The more you monitor, the more you get to know your data and you can refine non-stop what you should be looking at.

Their pricing model is based on how many metrics you keep track of, so I'm not sure how biased his speech was, but the idea is interesting nonetheless.

CRDTs

Then Dan Brown came again (he was here the year before as well) to talk about CRDT, or Conflict-free Replicated Data Types. This gives a set of guidelines to know how to reconcile conflicts across two different versions of a data in an eventually consistent architecture.

By defining a standard set of rules, conflictual merges can be reasoned about with the same outcome by everybody. When you have to changes on a boolean value, let's use true by default. When changing the value of a counter, let's always use the most positive (or negative) value. When changing the value of a simple key/value pair, let's say that the last write wins. For arrays, if you happen to have several conflicting add/remove jobs, give priority to the additions.

This will not avoid conflicts, but will give a commonly known set of rules to automatically handle them, without requiring manual interaction.

Scaling bitcoins

Then was Gilles Cadignan, about how to make a proof of existence using bitcoins. He started with the assumption that everybody knew what bitcoin is and roughly how it works. That was my case, I still only roughly get how it works.

In a nutshell, he explained how to embed some document hashes into the bitcoin chain to prove that a document existed at a given date. Not sure I can give more explanation than that, sorry.

Monorepos and many repos

Then, Fabien Potencier from Symfony explained how the monorepo organization of Symfony is working. They currently have 43 projects in the same monorepo. They use this repo for development, not for deployment. They have scripts to split this big monorepo into individual repositories.

They still actually use both one big monorepo and several small many repos. I'm not sure I get the story completely straight, because when I talked about it with other attendees, we all understood something different. But what I get was that the monorepo is the source of truth, this is where all the code related to the Symfony project is hosted. It makes synchronizing dependencies and running tests much easier as everything is in the same place.

But they still automatically split this main monorepo into as many repos as there are projects. Those projects actually reference the same commit id as the one in the main monorepo. By doing so they still keep a logical link between commits in two repos, but they can give specific ACL to people on specific parts of the project.

What I did not understand is how you contribute. Do you submit a PR to the main monorepo and it will trickle down to the simple repo, or do you submit a PR to the small repo and it will then in turn submit a PR to the main one?

Juan Benet

After that, it was time to get back to the real talks. The next one was by Juan Benet, about IPFS, the InterPlanetary File System. One of the most awesome and inspiring talks of the day. To be honest, there was so much awesome content in it that it could have lasted the whole day.

He started by reminding us how bad the whole concept of centralizing data is. Distributed data is not enough, you just create local copies of your data, but they still all depend on a central point. What we need is decentralized. We have more and more connected devices in our lives, but still, it is not possible, as of today, to easily connect two phones together, directly. We still have to pass through external servers to send files. Considering the machine power of the devices we have in our pockets, this is insane. Those devices should be able to speak to each other without requiring a third party.

Centralization is also a security issue. Even if the connection is encrypted, the data stored on the machine is not. It has to be stored in plain somewhere, which means that it can be accessed, copied or altered.

Most of the time, we cannot directly access the data. We always have to use a specific application to access its data. There is no way to directly connect to a DB of a distant server for example, we have to go through their API (when it exists).

Webpages are getting bigger and bigger, but we do not really care because we have faster and faster data connection. Except when we don't. When we are in the countryside or in the subway for example. Or living in a country where the data connection infrastructure is not as good. And we're not only talking about third world countries here, but every country after a natural disaster such as an earthquake. And it's in those very specific moments that you do need to have your means of communication working. But there are also the human disasters to take into account, the government oppression, the freedom of speech to defend...

In our current web, URLs are not eternal. Links breaks all the time because website evolve, or because url shorteners are no longer maintained.

Well, that's a huge list of problems that I can only agree with. All of this comes from the same root cause, that all the online resources are linked to an address. Internet is an awesome pool of knowledge, but it is still very awkward and old-fashion in certain aspects. 50 years ago if I were to tell you "Oh, I read this book, it is awesome, you should read it too", you just had to go to the closest library and borrow the book. Today with the way internet is working you would have to go to the very specific library I'll point to you, even if the same content could have been found somewhere else. We are not pointing at content anymore, but at addresses to find that content.

It's a big problem, and there is a way to fix this, that draw its inspiration from git. SVN was centralized, and it exhibited all the issues I talked about earlier. Git and its decentralized model fixed it all.

IPFS would be like git, but for content. Each object would be linked to another through crypto hashes, like commit hashes, and that way ensure the integrity of the whole. You couldn't just change something in the chain of commits without everybody knowing. And when you would talk about a specific file, through its hash, everybody would know what you are talking about. Because it would be distributed, there would not be any central source to get data from, you could get it directly from any of your peers that have it as well.

There is already a lot of P2P systems that works through this logic, like bitcoins. OpenBazaar is an eBay-like, distributed and using bitcoins as a currency. The beauty of such a system is that you can still add some central nodes, like GitHub does for git projects, but they won't become SPOF, they are just here for performance and convenience.

libp2p is a library that integrates a lot of existing P2P protocols to build this IPFS. All of them are compatible and allow sharing of documents through a forest of Merkle trees from various compatibles origins.

This idea of using a git structure for various usages was discussed by a few speakers, but this presentation really went deeper into it. Two years ago everybody was talking about Docker in their presentations like it will be the next big thing, I really hope that IPFS will be a reality in two years. This will just be one of the greatest improvement in the worlds of data sharing, hosting and security.

Such networks are already in place for some blogs, web apps and scientific papers. Following the talk of Diogo Monica at dotSecurity, such a system will also be of great value for package managers.

Such an awesome talk really, this is my personal highlight of the whole day.

Greg Lindhal

Next talk was also one of my highlights. It was from Greg Lindhal, and explained how the Internet Archive works, from the inside.

The Internet Archive is a non profit library that aims to store everything that is produced on the internet. It contains more than 2 million videos, books and audio recording, more than 3 million hours of television and 478 billions of website captures. Overall, this weight around 25 petabytes of data.

One of their main focus is on not losing any data, ever. They store the data on two geographic locations, and store it on two different physical disks on those locations. They extract metadata from the documents and have a centralized server that contains only the metadata and information about where to find the complete file.

Metadata information is also stored alongside the data itself, so if the centralized server gets corrupted, its content can still be reconstructed from the raw data.

They get their initial data from various crawlers, some are their owns, other are from external sources, either professional (like Alexa) or volunteers.

They have a lot of what they call derived data. From a given source, they can run OCR, extract the transcript, or other kind of data. To do so, they need to operate on a copy of the original data, to avoid corrupting the data in case something goes wrong.

They currently have issues with their search, which is not very efficient. They do manually build an index of all their resources in a text file of 60TB compressed. It is so big they have to build an index of the index itself.

In the future they would like to do a partnership with major browsers, that could provide a fallback on a previous version of a website, in case of a 404 error. But before being able to provide that, they need to figure out how to scale the lookup time.

They are currently operating on the maximum capacity. They plan to move on SSD, but this is still too expensive. They are also investigating migrating to a NoSQL database to replace their manual text index file. It currently takes 100 days, just to index content. But this is an old project, with hacks built on top of hacks built on top of hacks. Changing the stack means backporting all the (undocumented) hacks. Technical debt is not about technology, it's about people, and how they used the technology along the years.

As the speaker was saying, all of their projects, even the smallest one can be considered big data. They tried to move to ElasticSearch, but 100GB of their data exponentially explode to 12TB once put into ES.

Surprisingly, they do not receive that many take down requests for copyright infringement, but this is mainly because their search is so bad, that it is nearly impossible to find something. I especially like this quote by the speaker about that:

First thing you do when building a website search engine with ElasticSearch is to replace the default ES algorithm.

Really nice overview of how this massive project operates. The amount of data stored is extraordinary, and I've always wondered how a non-profit managed to handle this. The answer is: they struggle.

Sean Owen

Then it was a talk from Sean Owen, from Cloudera. He mainly talked about machine learning in the context of content recommendation for music genres. It went quickly too technical for me to follow the main idea.

He told that what started as a machine learning project, quickly became a big data project. They realized that to build a relevant content recommendation system, they will need data from their users. They use Spark to handle the processing of the data, because the technology is apparently well suited for scaling this kind of recommendation and machine learning issue.

As I said, he quickly started giving a mathematical explanation of how to compute two matrix of music genres, with specific tips and tricks to make it faster to compute. I cannot remember the exact tricks of this specific use-case, except that he suggested to always use the native math libs of Sparks instead of the JVM for anything math-heavy related.

So yeah, sorry this recap is not as thorough as the others, that's really all I can say about it.

Spencer Kimball

The next talk was a joke. Spencer Kimball was supposed to tell us more about CockroachDB, but he seemed like he had a plane to catch. He did in less than 20 minutes what was supposed to be a 1 hour long talk.

We barely had time to read a slide before he jumped to the next. The only thing I grasped from his talk was that he knew what he was talking about. Good for him, because honestly, I think he was the only one.

Gleb Budman

Fortunately, the next talk was its exact opposite and was one of my favorites from the day. Gleb Budman, from BackBlaze gave an overview of how they built BackBlaze from the first days.

BackBlaze is a cloud backup system. They offer unlimited backup for 5$/month (unfortunately not compatible with Linux, otherwise I would already be a customer). What is really interesting is their approach into building such a system, in an iterative process.

They first had to choose where to store the data. They couldn't go to Amazon because for 5$ a month, they could only get 30GB, and they needed to offer infinite storage space, because you never know how much data you'll have to save. And you want a backup system that "just works", without you worrying about disk space.

So they started to investigate into buying their own hardware. They quickly realized that they could buy a 1TB drive for 100$ in a local shop, while it would cost more than 1000$ for the same capacity for its server-side version.

They never imagined that they would start building their own hardware. Amazon already does that, and there was no way they could be more cost efficient than Amazon. But it was either trying, or closing the company. So they tried.

They started with external drives and cascading USB hubs. Didn't work.

So they started thinking about what they do not need. They are only storing data, they do not need to run application on their hardware. The data will only be accessible from time to time, not continuously. The various machines will not need to be able to talk to each other directly.

But they do need to be cost and space efficient. They need to be able to store as much data as possible in the smallest possible space, without being too expensive. So they bought a bulk of hard drives. Not high quality ones, but commodity parts. They created a custom case, made out of wood, to host as many drives as possible.

This worked well, but didn't scale really well. They will need more and more of those cases if they want to grow. So they decided to do some Agile, but for hardware. They contacted a company that could build a metal case from the wood prototype. And in small iterations of 4 weeks, they manage to learn a lot about what they needed, by testing it constantly, and improving each case from the knowledge they got from the previous case. They tested different shops, different 3D printing techniques, and regularly improved the hard drive case.

But then developers started to ask for an API, to directly access the data. So they needed to keep iterating on the case, but now to hold hardware that could host both the data and run a webserver.

They managed to fit 60 hard drive in a box, or what they call a pod. Because it's commodity hardware, it will fail. So they replicate the data across the drives. For each chunk of 20 drives, they can afford 3 of them down at any time. The data is replicated enough so that they could rebuild the missing pieces as long as 17 drives are working.

He then gave more details about some real life issues they had when building the pods. Like forgetting to put a hole to set a power button, or putting a coat of paint that was too thick and prevented the case to fit in the datacenter. Or how a flood in Thailand stopped the worldwide production of hard drives and how they had to manually go buy external drives and rip them out to get the hard drives to put in the pods.

Overall, his talk was really inspiring. Telling us that there is nothing more important than field knowledge. Go test your product on the field as soon as possible. It can work with hardware as well as with software. Find ways to build, even if not perfect, you will learn and you will improve it over time. Toss the unnecessary, don't buy things that are too expensive and provide features you don't need. Create prototypes fast, and often.

Ted Dunning

Then Ted Dunning talked about real time processing, and how streams are the future. The talk seemed really meta and high level and hard to follow.

He started by saying that everything in the world works in a symmetric way, with an associated conservative law, like energy and time. And that this is true both in the microscopic and macroscopic world. He then throws a few dollar bills on the floor, telling us that if we had to pick those bills, the most clever way would be to pick the highest value bills first. I told you it was meta.

The idea behind the bills show is that, if bytes were money, we should pick the best bytes first. A data processing system should first take the more interesting data, and then continue by picking the less interesting data. This would create a graph were the value we get from the data is high at first, and then just hit a plateau where we got less and less value per data. The flatter the graph goes, the more expensive it gets to get value.

He then went on talking about the fact that data should never be altered. That data should only be reasoned about in terms of now, after and before. That all processing of data is actually a stream, and that data will just keep growing and that scaling is inevitable.

He also went on talking about the communication cost of developers. In a perfect world, putting more developer on a task should make this task faster to resolve. In practice, this adds a communication cost. There is an optimum number of developers for a given task where the boost in productivity outweighs the cost of the communication. Each company, and even each project, should find this optimum.

He concluded by saying that even if REST is nice, and that you can technically do anything with it, it still creates a communication cost in between all the nodes that needs to communicate. On the other hand, streaming (through something like Kafka), removes the need for coordination, or acknowledgement, and will win this part in the future.

To be honest, I had a hard time following where he wanted to bring us with this talk. I am still not sure what is point was.

Eliot Horowitz

The next talk was easier to follow, even if I didn't really share the excitement of the speaker. Eliot Horowitz is the co-founder and CTO of MongoDB.

He talked about how we all already have microservices in the form of third parties in our infra. We have analytics in GA, project management in JIRA, various tools for the NPS, the emailing and a lot of other applications.

The issue with that is how to keep the data consistent across all those services, and more importantly how to search into it all at once. Each service has its own part of the data, and see it through his own system. It is very hard to get a big picture of it all, and link data together.

You could build a regular report by fetching data from all sources, aggregate them and output a coherent set of values. This would take some time and money, and will be fixed in time. This is not the way to search and explore your data.

You could build a data warehouse, where you put all the structured data you got from building the reports. This would let you search into it. But every time you will add a new source or change the schema of the data, this will create inconsistencies in your warehouse.

On the other hand, you could build a data lake, where you put everything, with various schemas. Unfortunately, the lake will quickly become a dump. You're actually just building a drowned warehouse.

So let's start again, and let's not assume you need to put all the data in the same place. By keeping the data where it is, you offer more flexibility to the usages. You can add new services that will handle new type of data.

Mongo Aggregate is the service he wanted to tell us about. It is a new pipeline in mongoDB that lets you query data from various (external) sources. It is built to let you link several cohorts. For example knowing if the users that did something in system A, are also the same that did something else in system B. For example, are the users that read the release note the same that give a high NPS?

To do so, mongo has to actually query this external services. A lot. But because the whole process of getting a subset of users from one system and checking in another system if they share a common attribute is wrapped into mongo, they can optimize the query on several levels. How? I don't know, I think he only mentioned caching. I wonder how this handle third party failures.

I'm always highly skeptical about tools that are branded as "you can anything with it, we just take care of everything". Connection to third parties API is trivial, except when it fails. And it fails a lot, so having all this hidden inside mongoDB does not seem an attractive feature to me.

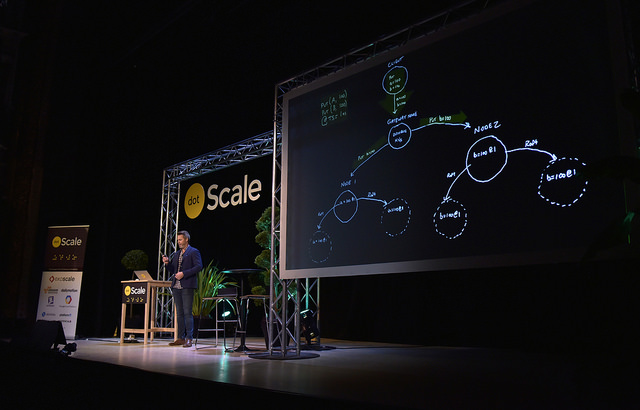

Eric Brewer

Last talk of the day was by Eric Brewer, VP of Infrastructure at Google. He talked about immutable containers.

For him, we should really not focus on the containers, but on the services they are running and exposing. We should not care about which machine is hosting a container, we should just care about the service it exposes.

He discusses grouping containers into pods, that also share a data volume. All containers of a pod are collocated on the same machine, so each knows about the IP address and exposed ports of the others.

You then start to build services on top of pods. The pods are stateless, they are self-containers, even if their internal containers are stateful. Now, you can just duplicate the pods and put a load-balancer in front of them. Pods are interchangeable, because they are immutable. I could just restart one at any time. And I name them based on the service they host, not their inner components.

If we go one level higher, a network of pods should also be immutable because each of its parts is immutable. Because of this, you could build your own infra and test that it works correctly before actually deploying it. When you build, you actually just build a graph of all your pods together.

This all looks well on paper, but I often hear that immutability is the answer to all software problems, like asynchronous code was a few years ago, so this just looks a bit too magical.

Anyway, he finished with a demo of how he could do a hot version update on hundred of pods without downtime, by replacing each non-used pod one after the other and replacing it with one with the new version.

He still finished on an interesting note about hard drive and datacenter reliability. In the future, we will store less and less data on our laptops and more and more data in the cloud. Drives in datacenters will become the main storage point, and those are already pretty reliable today. They are even often more reliable than the rest of the structure of the datacenter. So there will be no need to further improve their reliability; instead we should reduce their size, make them cheaper, make them use less energy. In the end they only need to be as reliable as the datacenter that is holding them.

Conclusion

And that's it, the end of the day. This was a pretty long day, especially considering that we also had the dotSecurity the Friday before. Next year, there will even have a dotAI on the day after. Not sure I'll be able to do the three days in a row.

The main subjects were about containers and how they handle state. How going for fully stateless is not actually possible and containers should embrace their data, through pods or other grouping pattern. Merkle trees and git-like structure where also a hot topic, and one that got my attention.

Overall I have the same feeling than after dotJS. Lots of talks, but only a few really inspiring. Those talks are awesome, don't get me wrong, and they make the conference worth it, but the ratio is less interesting than at dotSecurity for example. I think I will come back next year, but not sure I'll go to dotAI.

Want to add something ? Feel free to get in touch on Twitter : @pixelastic